In 2022 a consortium of companies ran an international competition, called the ZPrize, to advance the state of the art in “zero-knowledge” cryptography. We decided to have a go in our free time at submitting solutions to both the Multi-Scalar Multiplication (MSM) and Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) tracks, using the same open source Hardcaml libraries that Jane Street uses for our own FPGA development. We believe by using Hardcaml we were able to more efficiently and robustly come up with designs in the short competition period. These designs also interact with the standard vendor RTL flow and so we hope they will be useful to others.

Our MSM solution, implemented on the BLS12-377 curve, beats all current FPGA state of the art, including the recently released Cyclone MSM and PipeMSM. It’s able to calculate 4 rounds of 226 MSMs 20.331s, an average of 5.083s per MSM, and won first place in the ZPrize MSM track. Our power-area-performance balanced NTT solution took second place in the ZPrize NTT track. Full results are available here.

Our results and a bit of background on the competition are summarized below. For more detailed reading, we have created a Hardcaml ZPrize website.

Zero-knowledge proofs

Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) are powerful cryptography tools that allow a prover to prove that a certain statement is true without revealing any other information to the verifier. For example for a given function F and publicly known x, a prover can show F(x,w) = y, without revealing w to the verifier.

This property means ZKPs are attractive in contexts where online privacy is paramount, for instance anonymous voting. They also form the backbone of certain blockchain features (zk-Rollups) and “Web3” applications, and have been becoming increasingly popular in recent years.

One class of ZKP getting attention lately is called “Zero-knowledge Succinct Non-interactive Arguments of Knowledge” (zk-SNARKs). These require no interaction between the prover and verifier, and are compact and quick to verify.

The problem is that while verifying is relatively fast, constructing the proof of a zk-SNARK can be quite time consuming—minutes or even hours when there is a large number of constraints. Most of this time is spent in the calculation of NTTs and MSMs (roughly 30% and 70% respectively). Current systems that use zk-SNARKs tend to have constraint sizes in the millions.

Before describing our specific solutions, we’ll briefly introduce the underlying cryptographic primitives.

Elliptic curve cryptography

Elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) allows for smaller keys compared to non-EC cryptography such as RSA (modular exponentiation based on plain Galois fields), to provide the same level of security. For example a small 228 bit ECC key requires as much time to crack as a much larger 2,380 bit RSA key. A smaller key here means cryptographic systems and the data transfer involved can be much more compact and faster.

All ECC calculations take place within Fp, a finite field of integers modulus a large prime p, and in particular are performed over cyclic groups which have a generator g (all elements in the group can be generated from this point).

Basic operations on an elliptic curve are point addition and point doubling, which are used repeatedly in the MSM algorithm. In order to implement point operations, we are performing multiplications and additions modulo a prime. These operations can further be optimized with efficient modulo reduction algorithms such as Barrett or Montgomery, and better-than-O(n2) multiplication techniques such as the Karatsuba algorithm.

zk-SNARKs make use of ECC primitives, through several well-known prover algorithms such as Groth16. But the problem is the more complex zk-SNARK we want to implement, the more constraints we need—which translates directly into very large polynomials.

It’s the operations on these large polynomials (order 226 and up) that require fast MSM and NTT solutions. NTTs are used to achieve an O(NlogN) rather than O(n2) time complexity in polynomial multiplication; MSMs are needed for the exponentiation of the elliptic curve points, described more in the next section.

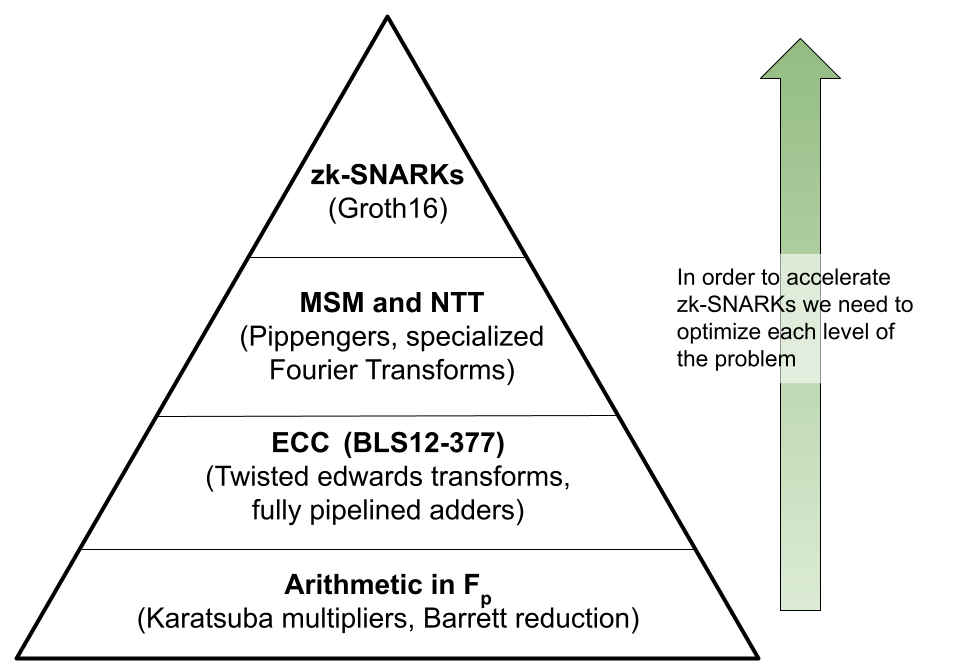

The diagram below shows that in order to accelerate zk-SNARKs, we need to focus on both MSM and NTT problems, which in turn require novel optimizations in their ECC primitives—a full-stack solution.

Our solutions to the MSM and NTT problems

MSM

In general, the MSM problem is to take a list of scalars and points and compute the sum of each of the points scaled by its corresponding scalar. For the MSM prize track, we were tasked with performing the MSM computation over a fixed set of 226 elliptic curve points from the BLS 12-377 G1 curve and a randomly sampled set of scalars from the corresponding scalar field. (Because the points are fixed, this is sometimes referred to as a “fixed-base MSM”.)

To solve this problem, we implemented a heavily optimized version of Pippenger’s algorithm (explained here).

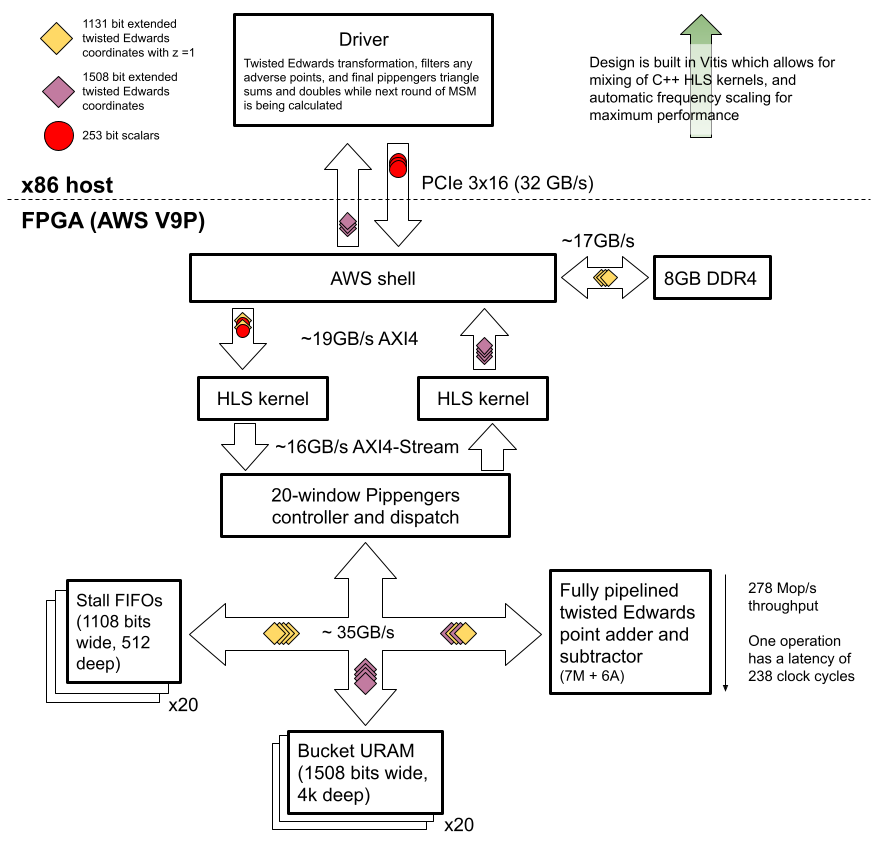

We implemented a solution that uses the FPGA to do the vast majority of the computational work, while the host does a much smaller set of computations to obtain the final result. By splitting the work between the x86 host and the FPGA, we were able to focus on optimizing the algorithm for implementation on an FPGA while leaving seldom-seen corner cases to the host. One challenge we had to overcome with fragmenting the computation like this was how to architect system communication to allow the FPGA to start streaming and processing the next round of calculations, while in parallel having the host finish up the previous batch.

The core of our design is a fully pipelined, optimized elliptic curve point adder. The majority of the work in Pippenger’s algorithm consists of adding the points into buckets based on their coefficients. By performing all of these bucket accumulations on the FPGA, we accelerate the entire algorithm. However, because elliptic curve point addition is a complex operation, our pipelined adder has over 200 pipeline stages! Flushing the pipeline every time we hit a data hazard while adding points into the same bucket would destroy our throughput, so we also implement a controller which coordinates stalling and adding points into buckets to avoid data hazards. The FPGA then streams these partial bucket sums back to the host, where they are combined to produce the final result.

We made a number of optimizations, both algorithmic and engineering-wise, across the full stack of the solution, including finite field operations, elliptic curve arithmetic, and Pippenger’s algorithm. For a detailed discussion of our techniques and optimizations, see our website.

Results

We implemented our MSM solution on an AWS f1.2xlarge instance which costs $1.65 per hour, over various input sizes up to 226 inputs. The FPGA card uses a V9P UltraScale+ Xilinx chip. We report both the total latency for 4 rounds of MSM, as well as the latency for a single round, over several different MSM sizes. “Masked 1 round latency” is the average of 4 rounds, taking into account our optimizations that allow host and FPGA work to be parallelized. “Unmasked 1 round latency” means we explicitly calculate one round, which shows the overhead of doing work on the host.

| Input size | 4 round latency (s) | Masked 1 round latency (s) | Unmasked 1 round latency (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 226 | 20.331 | 5.083 | 5.518 |

| 225 | 10.398 | 2.600 | 2.989 |

| 224 | 5.967 | 1.492 | 1.724 |

| 223 | 3.901 | 0.975 | 1.092 |

| 222 | 2.883 | 0.720 | 0.779 |

Average running power used by the FPGA design is 52 watts regardless of input size. For detailed resource usage and even more detailed latency breakdowns see our website.

NTT

The Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) is very similar to the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), except that it operates over a finite field instead of complex numbers. NTTs replace the normal twiddle factors you see in an FFT with a new finite primitive root of unity w, where w is the nth root of unity if wn = 1 modulo some large prime number. In this competition, we were required to use the Solinas prime 264-232+1.

Our NTT solution was written to target a C1100 FPGA accelerator card, and implements the 4-step algorithm over a 224 NTT.

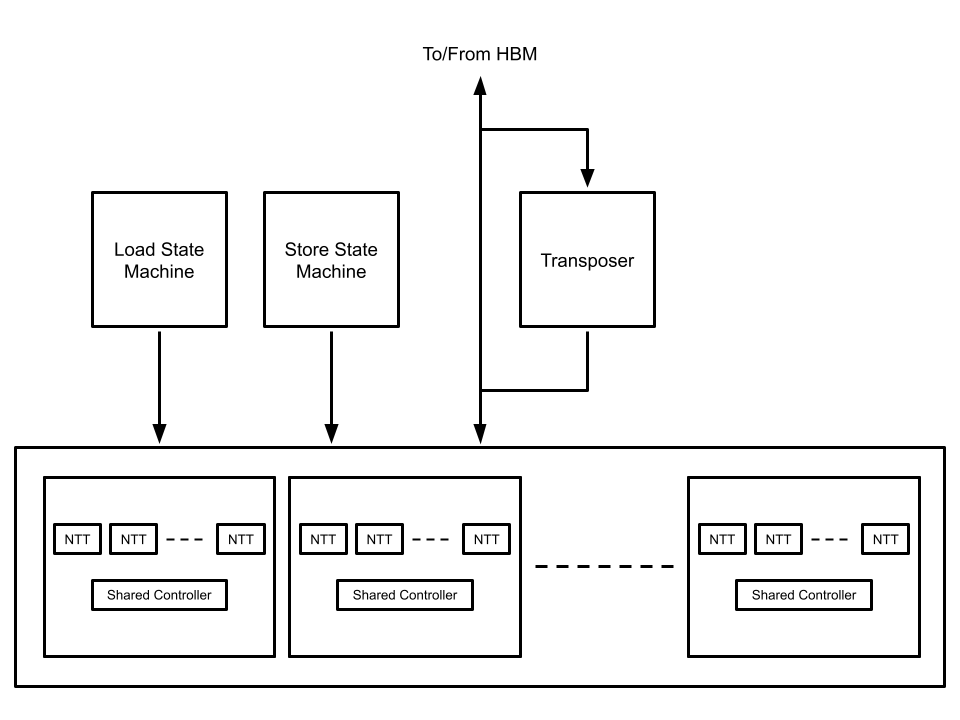

By choosing this algorithm we were able to decompose the original NTT into many smaller ones that can be run in parallel. The smaller NTTs, each of size 212, can easily fit in the available SRAM resources on the FPGA. These smaller transforms were implemented using the well-known Cooley-Tukey FFT algorithm adapted for a finite field.

We decided to implement 8 parallel cores as a cluster, as this matched our HBM bus width of 512 bits. Each core inputs and outputs 64 bits and has its own field multiplier and two adders. All the cores in a cluster share a single controller. We can then instantiate multiple clusters of cores over the FPGA to achieve high parallelism. The diagram below highlights the blocks and data-flow between off-chip memory (HBM) and on-chip SRAM.

We have a much more detailed writeup of the algorithms used, plus source code and instructions for building from scratch here.

Results

We experimented with different core counts on a single C1100 Varium card, with results listed below for a full 224 NTT:

| Cores | Latency (s) | Power (W) | LUTs | Registers | DSP | BRAM36 | URAM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0.2315 | 16.97 | 107291 | 141006 | 260 | 162 | 48 |

| 16 | 0.1238 | 18.19 | 126422 | 156149 | 512 | 162 | 96 |

| 32 | 0.0691 | 21.13 | 166488 | 184436 | 1028 | 162 | 192 |

| 64 | 0.0450 | 27.70 | 265523 | 246385 | 2052 | 162 | 384 |

Future work

Due to time constraints, there were a number of optimizations that we did not have a chance to experiment with. We discuss them at length on the corresponding page of our website.