The Dojima rice market, established around 1716, is widely considered to be the world’s first organized futures exchange. Instead of directly exchanging money for rice on the spot, merchants would agree on a price and future date at which rice and money would be exchanged. This allowed farmers and consumers to hedge their risk. As a result, information about the abundance or lack of rice would travel across the country as fast as rice merchants carried it.

In Kumagae Onna Amigasa, author Bunryu Nishiki describes how a rice merchant from Koriyama named Yomiji would convey these price signals from Dojima, Osaka to Koriyama in order to make profitable trades.

In order to get information about daily prices at the rice exchange, Yomiji hired a regular express messenger \... A minute after the rice exchange started the business of the day in Osaka, the messenger wearing red hat and red gloves ran like a flying bird and arrived at Kuragari Pass \... If he raised his left hand by 1 degree, it meant the rice price increased by 1 bu of silver. If he raised his right hand by 1 degree, it meant the rice price decreased by 1 bu of silver. His role was to inform Yomiji of the increases and decreases of rice prices. Yomiji saw the person's signals from the second floor of the wholesale store using a telescope which had a range of 10 miles, and bought or sold rice taking these price changes into consideration \... As Yomiji knew the rice prices earlier than anyone when the information was delivered to Kuragari Pass, there was not a single day that Yomiji did not make money. Other merchants had no idea about his scheme. They gave Yomiji the nickname "Forecasting Yomiji" and rice prices in Koriyama came to be greatly influenced by Yomiji's transactions. [0] [1]

Today, price signals can travel much faster than anyone can run, but still no faster than the light which entered Yomiji’s telescope. Information propagates through fiber optic cables that span the oceans. Using data from several futures exchanges around the world, we put together a visualization to show how this happens.

*

Some of the most heavily traded products in the world are equity index futures. An equity index, like the S&P 500, represents a weighted basket of stocks. For example, the S&P 500 is representative of the entire U.S. stock market, whereas the FTSE 100 Index is representative of publicly traded firms in the UK. An equity index future allows people to bet on, or hedge their exposure to, the price of these indices at a future point in time.

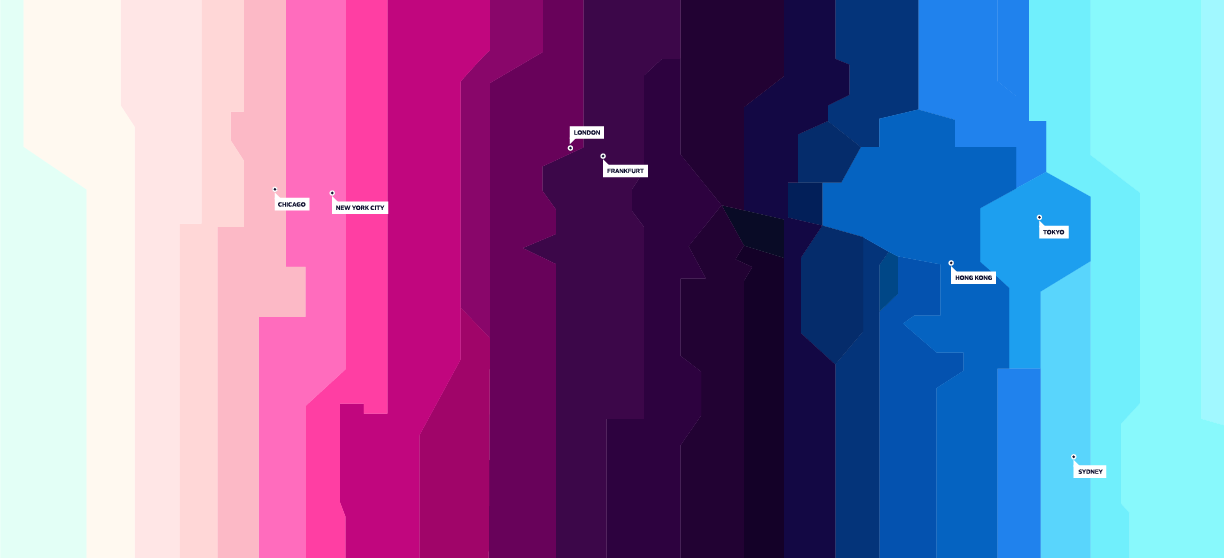

Like rice futures, equity index futures trade in many geographic locations. Futures contracts on the S&P 500 Index trade in Chicago. Futures on the FTSE 100 Index are traded just outside of London. Nikkei 225 futures are traded in Tokyo, Hang Seng China Enterprises futures in Hong Kong, ASX SPI 200 futures in Sydney, and Euro Stoxx 50 futures in Frankfurt.

But unlike rice, equity indices aren’t fungible with each other—you can’t freely substitute one basket of stocks for another. However, the prices of these indices are still closely related to each other, and often move in tandem—such moves might be driven by news or other exogenous factors. Part of Jane Street’s role in the markets is to keep these prices fair and in line with each other.

We can visualize the propagation of information between various equity index futures by examining their price movements. We say that the price has moved if it changes by more than 0.01% in five milliseconds. We can then correlate a movement in one future with a movement in another future, if the movements happen right after each other.

That’s what the visualization below shows. We selected some data during a Federal Reserve announcement because it’s a particularly volatile time, which makes it easier to observe this phenomenon. In this time span, price movements are primarily driven by the announcement, so we should expect information to flow outward from the S&P 500 to the rest of the world. For that reason, we centered the visualization around Chicago.

In this visualization, we use a green or red marker around each location to indicate whenever the price moves up or down (and we filter out movements which couldn’t be correlated with each other). As a visual aid, we draw two rings propagating outward from Chicago, the first one moving at the speed of light, and the second one moving at half the speed of light. The vertical stripes on the globe show time-zone boundaries.

We’ve slowed down the video to 1/30th of real time so that it’s easier to understand what’s going on. If you look closely, you can see that most price movements occur between the first and second rings. This shows us that information can never travel faster than the speed of light, but often isn’t far behind—fiber optic cables carry signals at an appreciable fraction of c.

---

[0] “The Dojima Rice Market and the Origins of Futures Trading,” Moss and Kintgen

[1] Bunryu Nishiki, Kumagae Onna Amigasa (Kumagae Lady’s Hat), written in 1706, translated by Mayuka Yamazaki