Imagine a system for editing and reviewing code where:

-

Every branch of every repo gets its own sandboxed directory. Your revision history in each branch, including uncommitted stuff, is persisted, as are build artifacts. When you switch contexts, each project is just as you left it.

-

Within your editor, you can pull up a global view of all your branches, your outstanding pull requests, and the pull requests you’re assigned to review. It’s one keystroke to view the summary for a pull, and one more to start editing any of its files right there under your cursor.

-

Code review happens entirely within the editor. You’re fed a series of diffs: one keystroke to approve, one keystroke to start editing. Dive in, make your changes, leave comments for the author, push, and move on.

We’ve actually developed this workflow at Jane Street, and it’s been used daily by hundreds of engineers for about two years now. It feels like what an integrated development environment is supposed to feel like. Making software today is as much about collaboration as it is about writing your own code. But most developers are forced to switch from their editor to a web browser to read someone else’s code, and switch back if they want to play with it themselves.

Code review that takes place in a browser isn’t just more inconvenient, it’s often shallower, too: to really understand a piece of code you have to build it, run it, and explore it with your own hands, in your own editor. The system we’ve built at Jane Street is designed to make that level of engagement seamless.

The trouble is that it’s pretty coupled to our somewhat uncommon toolchain: we use Mercurial for revision control; instead of submitting pull requests to Github, we submit “features” to Iron, a code review system that we wrote in OCaml; and to tie it all together, we use a UI called “Feature Explorer” that we built on top of Emacs.

The goal of this post, then, is just to show off what the result looks like – to show you what kind of workflow is possible – in the hope that it inspires similar tools in other ecosystems. The truth is that after writing code at work this way for a while, you start to wish that you had something similar at home. But there’s nothing quite like it for Git and Github and editors like Vim or Textmate or VS Code.

What Git and Github could look like with truly deep editor integration

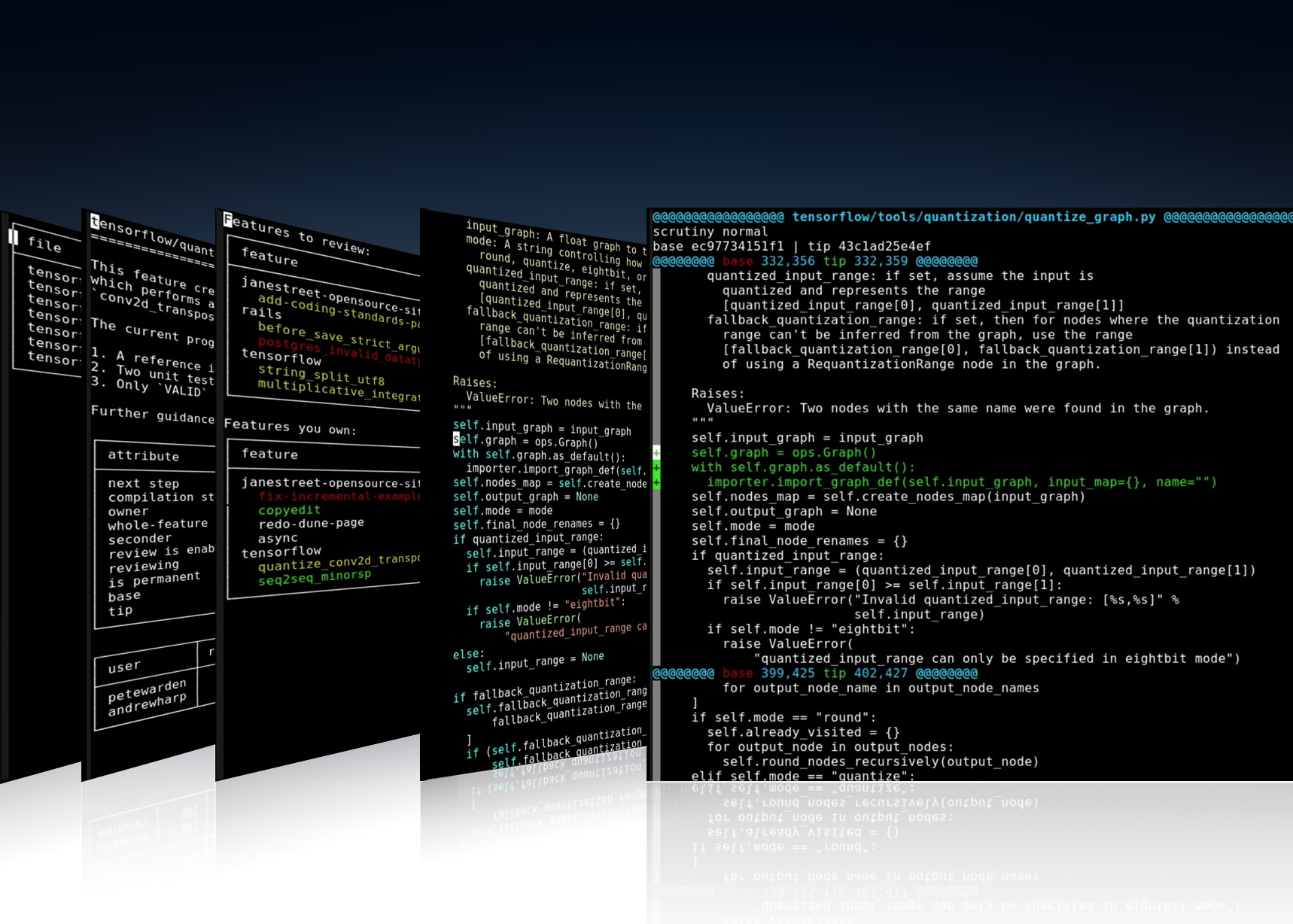

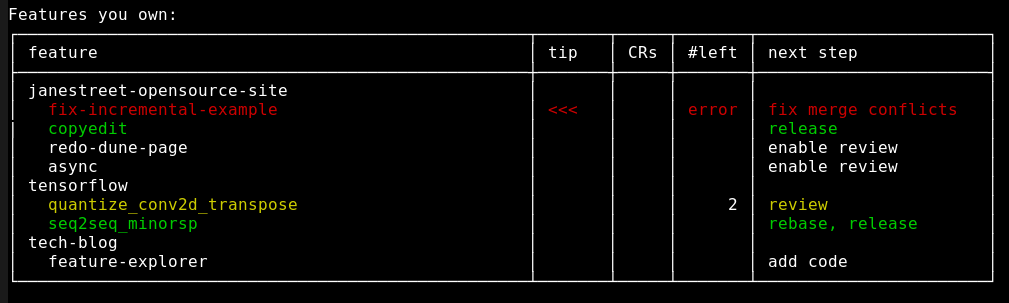

When you walk around the office here, there’s one window you’ll see open on every developer’s screen:

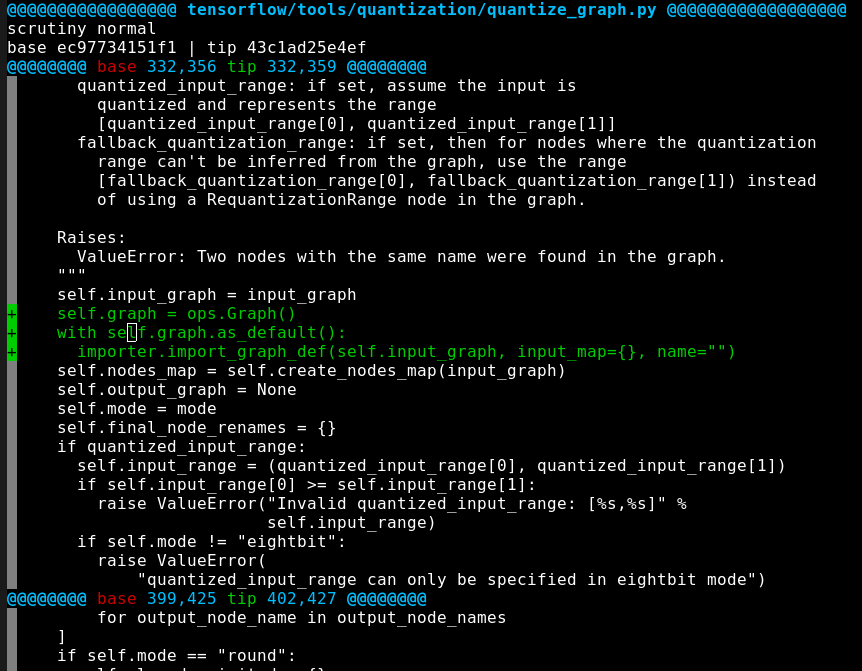

This is your todo in Feature Explorer. At the very top are the features you’ve been assigned to review, and below that are the features you own.

(Note that we call everything a “feature,” but really they come in two flavors: features that are ready for review are the equivalent of pull requests, and features that you’re just privately hacking away on are the equivalent of branches.)

It looks pretty dull but even here there’s actually a lot of

power. Notice how some of the features are indented a bit? That’s

because they belong to different repositories. To create a new repo,

or a new branch within an existing repo, you need only move your

cursor to the appropriate line and hit !c. Navigating across repos

is as cheap as navigating across branches.

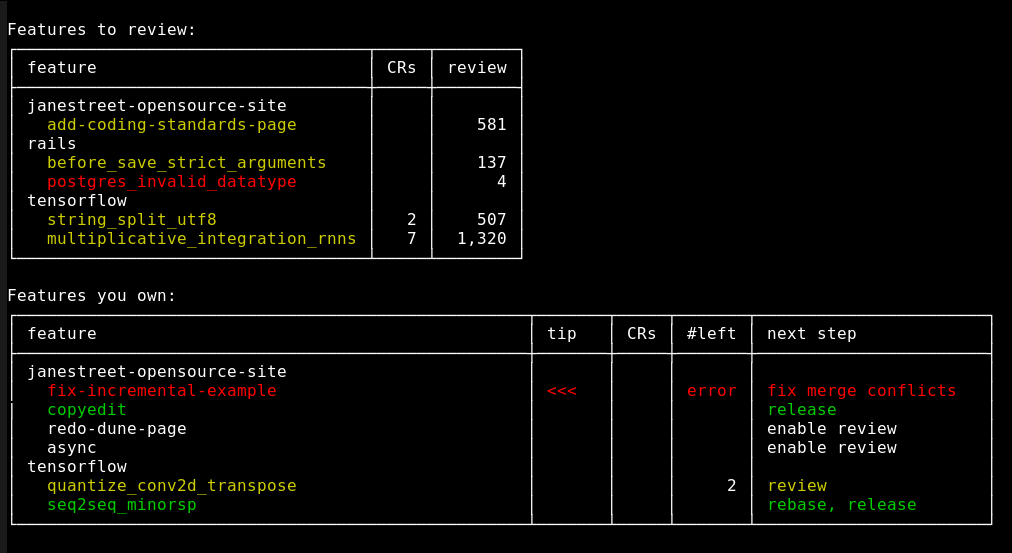

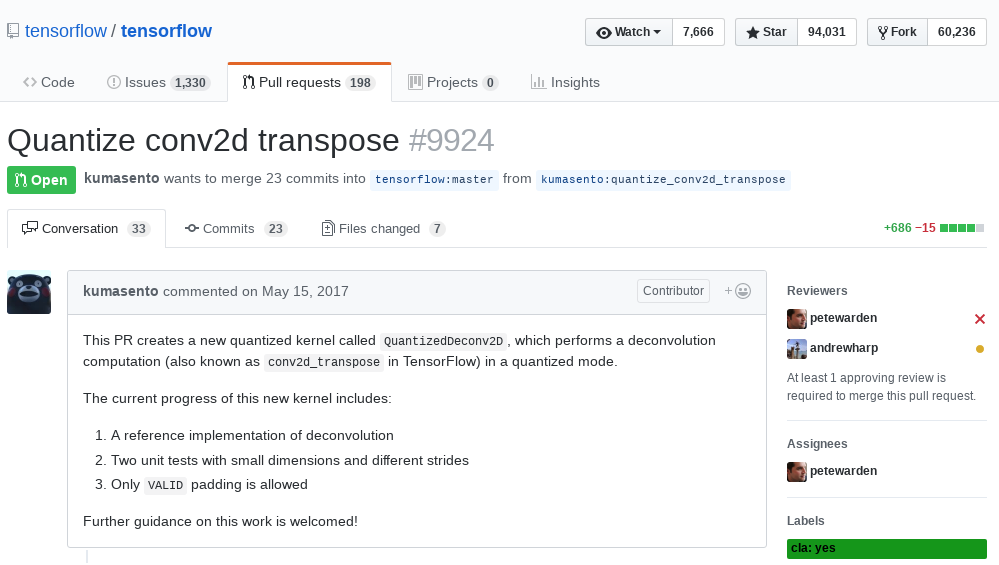

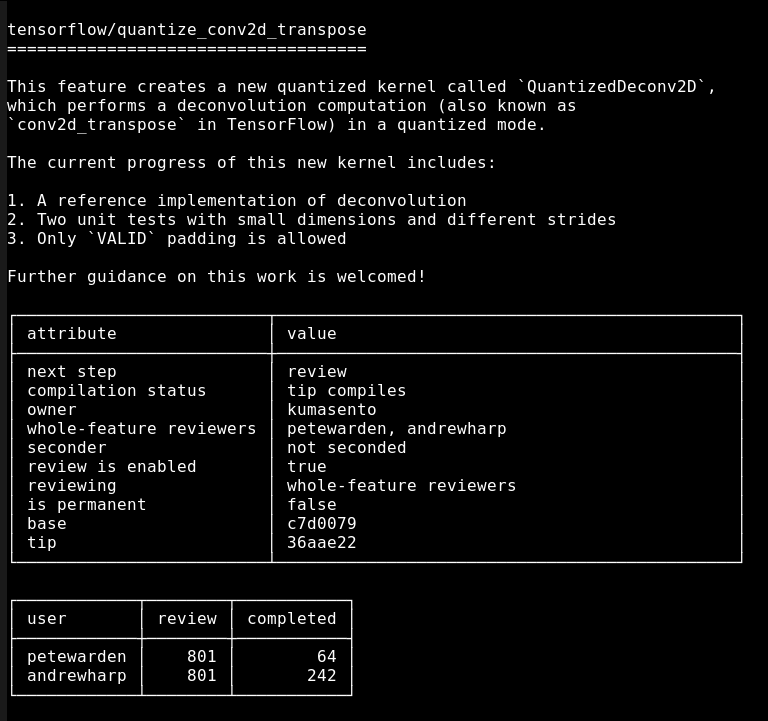

When you drill down into a feature, you see a page just like the one you see on Github for a pull request:

(What a Github pull request would look like if it were a Feature Explorer feature.)

Of course the difference is that here, that “page” is just a buffer in your editor. Which means you can hit Enter and, instead of getting a list of inert diffs in your web browser, you get diffs that can take you, in a single keystroke, to the very lines that were changed – loaded right there in your editor.

What’s more, the file you’re looking at isn’t some global copy – it’s the file for that branch. You didn’t have to think about it but you are already in the feature’s sandbox. Any changes you make are relative to that feature’s tip revision, and won’t affect any other features.

It’s worth dwelling on that for a second. All you did was hit Enter a few times, but it’s as if you performed four steps at radically different levels, all at once:

-

You used a Github-esque code review tool to get an overall view of what the feature (the pull request) does, including the files it changes.

-

You used a Git-esque revision control tool to check out (

git checkout) the specific repo and branch for that pull request. -

You used a file system to switch into the relevant directory where that repo & branch live (

cd ...) so that you can compile, run tests, manage revision history, etc., within a sandbox. -

You used an editor to load the file you care about into a buffer where you can actually make changes, use code completion, and so on.

These levels are blended so seamlessly that the distinctions between them fall away. When you navigate from feature to feature, you don’t have to worry about where you are in your file system, or what revision you’re on. All you’re thinking about is the code you’re looking at. You get used to thinking of the world not in terms of repositories and branches and directories, but in terms of features, i.e., units of functionality.

This makes it almost trivial to switch contexts. Let’s say I want to bring up a coworker’s pull request on a completely different repo. I split my Emacs window, navigate to the global todo, cursor over to her feature, Enter, Enter, and now I’ve got a diff, or the underlying file itself, loaded in my buffer. I can make changes to the file and push them, I can run the build against my coworker’s changes, etc., all without affecting anything about my feature; everything I touch is sandboxed to the world of her pull request. When I’m done, I close the window and get back to what I was doing. I literally never had to leave my editor.

You might think, hey, Atom has a slick new Github integration! Isn’t that the same thing?

Atom’s Github integration, as much an improvement as it is, is not a whole lot more than a browser window that happens to be inside your editor. Navigating to a pull request inside of the Github window doesn’t change “where you are” on disk; you can’t just navigate from repo to repo and, right there in your editor, pull up a file in the exact state it’s in in that pull request.

Once you can do that, you’ll wish the functionality existed everywhere people write code.

The lifecycle of a pull request in Feature Explorer

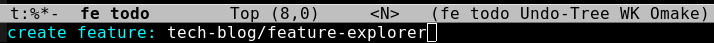

Let’s go back to the main todo and create a new feature. This is like

creating a new branch in git and a pull request in Github at the same

time. Just hit !c and give the feature a name, specifying which repo

it’s a part of.

When you hit Enter, already Iron has created a “workspace” for the new feature. Under the hood, workspaces are managed using a Mercurial extension called ShareExtension; the git equivalent would be to have multiple clones of the same repo on the same disk.

The way it works at Jane Street is that each user has a ~/workspaces directory on their disk. In ~/workspaces/REPO/+clone+/ there’s a full clone of the repo; then you do your work in ~/workspaces/REPO/BRANCH1/+share+ and ~/workspaces/REPO/BRANCH2/+share+/ and so on.

Those +share+ directories have very small /.hg directories compared to the main +clone+ one, because the versions in the +share+ directories are mostly made up of pointers to the +clone+ directories.

Since each workspace is a literal directory on disk, just by cd‘ing

you can go from one to the other and get a totally independent

workspace where you can create files, run the build, and so on.

Back in the main todo, you’ll see the feature you just created in the list of features you own.

There’s a “next step” column because a feature can be in a bunch of different states:

-

It might be currently under review. In this case, you’ll see how many reviewers are left.

-

It might be ready to release. All your code has been reviewed and approved: if you have the right permissions, just hit

!rlto “release” (i.e., merge the pull into master). -

It might be brand new, waiting for you to add code or enable review. A feature where review hasn’t been enabled is just like a branch you’re privately working on, rather than being a pull request. It isn’t visible to other people. Get in there and start hacking.

Features that are red have a failing build, the yellow ones are under review, the green ones are ready to release, and the white ones are works in progress.

To add files to your newly created pull request, just nav to its main page and use your editor’s keybindings to create a new file.

When you do that, you’ll notice that your root directory has changed to ~/workspaces/REPO/BRANCH/+share+/ because you’re in the sandbox.

To “submit a pull request,” you need only “enable review,” i.e., hit

!e on the feature’s main page – suddenly, the feature will be

publicly visible and will show up in other people’s todos. What’s neat

about this workflow is that it’s just as easy to disable review, say

if someone’s comments in code review led to a major rethink of how to

approach the feature. You can go quiet, hack hack hack, and re-enable

once you’re ready to show your code to the world again.

Code Review

We put code review at the top of your todo and color it yellow as a bit of a nudge. The idea is that someone else’s code that’s almost fully baked and almost ready to be released is basically a hair-on-fire priority compared to code that you’ve just started writing. It’s worth interrupting you for.

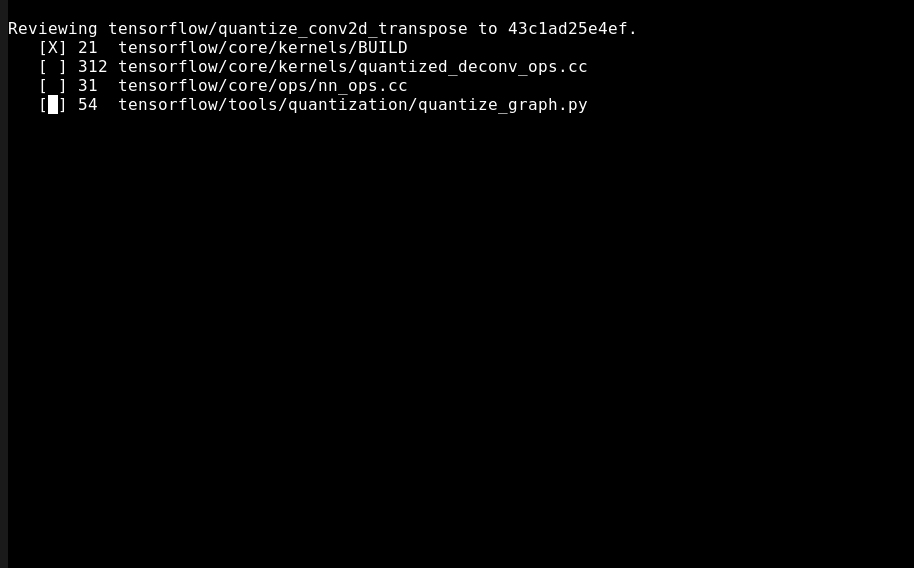

But we want to get you in and out of code review as quickly as

possible. Here’s how it works. In Feature Explorer, doing review is a

matter of going to the global todo, hitting Enter on one of the

features assigned to you, and pressing r. That’ll bring up a screen

like this:

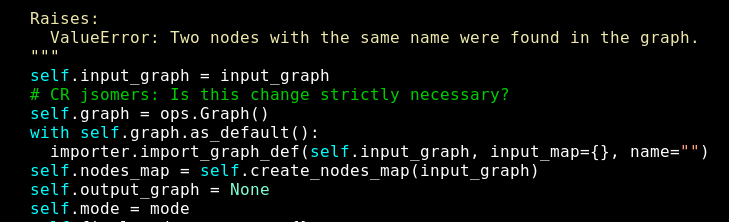

Each of those lines represents a patch for your review. Hit Enter again to read it:

There’s actually a lot of intelligence behind these screens – our code review system, Iron, uses a sophisticated algebra to calculate which diffs to show a reviewer based on what they’ve already reviewed, what merges and rebases there’ve been in the meantime, and the like – but the point to emphasize here is just that it’s all right there in your editor.

If you like what you see in a given patch, just hit !r to approve

it. If you don’t understand it, or want to leave a comment, you can

open the file by pressing e. The file will be opened in your editor

in a feature-specific sandbox. Feature Explorer will even put your

cursor on exactly the line affected by the patch.

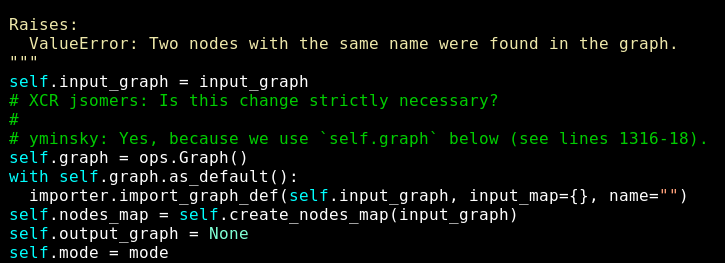

At Jane Street, reviewers leave notes as literal comments in the code. They’re distinguished by the special designation “CR” at the beginning of the comment. You can assign CRs, resolve them, etc., all just by editing the comment’s text using a special (but simple) syntax.

(Code review conversations take place in the code itself using special “CR” comments. Pending CRs show up in the assigned user’s todo.)

This system might seem primitive compared to Github’s in-browser commenting UI, but it means that you can do code review entirely within your editor. And since Feature Explorer is so tightly integrated with the code review system, it’s trivial to bring other people into the mix: if you assign someone a CR, the feature it’s a part of will immediately show up in their todo.

Go fork and prosper

There’s nothing special about Mercurial, Iron, or even Emacs that makes this system possible. Any extensible editor – like Vim, Atom, VS Code, Textmate – could support the core UI. Deep integrations for git already exist in most of these editors, and the Github API should be powerful enough to support an Iron-like code review system.

The highest-impact parts are in some ways the simplest, for example, the part that lets you navigate from a Github pull request down to a file in a specific branch on your local disk. If you’ve already got a clone of a repo, branching is cheap; creating sandboxed directories is cheap; and with a good enough Internet connection, listing pull requests and the files they affect is cheap. (One of the things we found with our system is that it didn’t really click until we had a sub-100ms code review server.) The rest is mostly editor glue.

Our system works well for us, but as sometimes happens with a piece of proprietary software built over a long time, it really only works for us. One hopes the idea is intriguing enough to encourage development elsewhere.