At the end of last year, we decided to try something new: a challenge that would run alongside Advent of Code, where we asked the community to show us how they could design hardware to solve the same problems. We had no idea what level of participation to expect, but we received a huge number of submissions, many of which were incredibly creative!

Before we get into the top submissions, here are statistics from the competition.

Overall we received 213 submissions, with 46 countries represented. The most came from the United States (28%), followed by India (23%) and the UK (11%). We also saw a wide range of participants: 59% were university or PhD students, while 32% were industry professionals (including several retired engineers). We were impressed to see participation from a few high school students as well.

At Jane Street we use Hardcaml every day, so it was exciting to also see how many submissions gave Hardcaml a try (we received 151 submissions that attempted at least one problem in it). As expected, Verilog, SystemVerilog, and VHDL were all very well represented, but on top of this we loved seeing the huge variety of other languages in the submissions: Chisel, Spade, BlueSpec, Veryl, Clash (including a very nice writeup by Tristan de Cacqueray), Spinal HDL, PipelineC, and even someone’s own experimental HDL language.

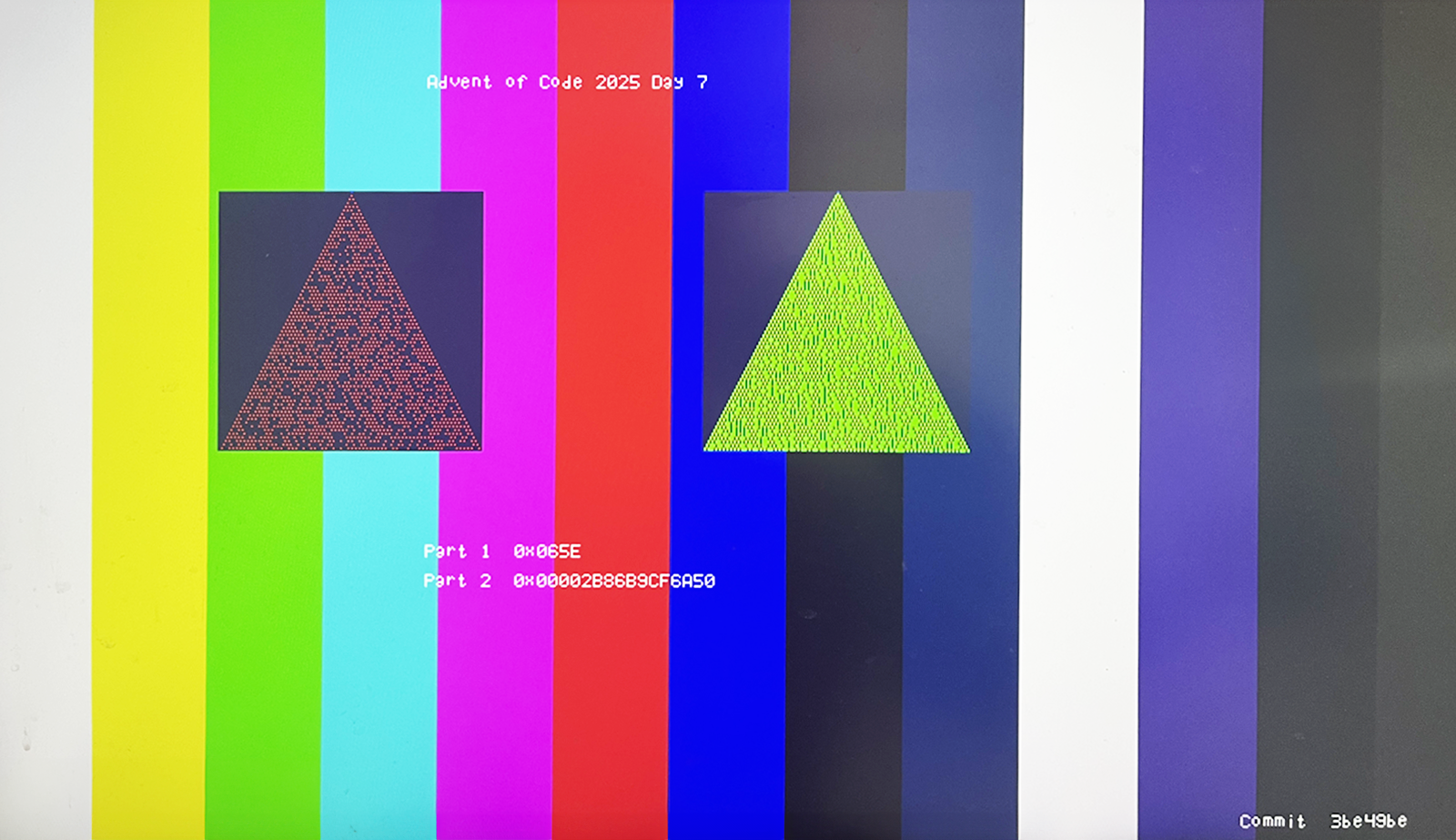

Some problems lent themselves to hardware implementation more easily than others. Days 1 and 3 were the most popular, both giving rise to “greedy algorithms” implemented using state machines. Days 4 and 7 were natural fits for hardware, using shift-register tricks to maximize throughput. On the other hand, days 8 and 11 both required classical graph algorithms, which took some clever tricks to translate into hardware (as seen in some of our featured solutions).

Judging the top submissions was really difficult—there were so many great ones. In the end, we looked for submissions with detailed write-ups that others can reference and learn from, as well as some trickier solves that took the solution further in some dimension, like demonstrating results on actual hardware or using unexpected implementation backends. In no particular order, these were our favorites:

Eric Pearson [Writeups]

Eric, a retired engineer from Canada, was one of the few participants to solve both parts of all 12 days. Working in SystemVerilog, he ran his designs across multiple platforms including ASIC flows, Altera, and Xilinx toolchains. His submission includes video documentation showing real-time solutions running on hardware—the Day 8 Part 2 video demonstrating the solution unfolding in real time was a particular highlight.

Frans Skarman [GitLab] [Website]

Frans, a postdoc researcher at Munich University of Applied Sciences, solved all 12 days entirely in Spade, a Rust-inspired HDL that he previously developed. He set himself the additional constraint of doing all parsing in hardware: every solution receives only raw input bytes and an EOF signal. His Day 10 solution is particularly creative: it generates Spade code from the puzzle input, then uses formal verification (bounded model checking) to find the shortest button sequence. After running the formal tools, the depth at which the assertion fails gives you the answer. Day 11 is so computationally intensive it requires nearly 64GB of RAM just to simulate! Frans also ran his designs on a ULX3S board with UART I/O, proving they work on real hardware.

Josef Gajdusek [GitHub] [Blog Post]

Josef, a hardware engineer from the Czech Republic, took a retro approach to the challenge: he built a physical PCB with 125 discrete 74-series logic chips to solve Day 1. He developed a clever pipeline that runs a Hardcaml design through Yosys and NextPNR, then uses a set of Python scripts to generate and wire up a PCB layout in KiCad. Despite the holiday timeline, he was able to get the PCBs manufactured and tested by the end of the competition! While he only tackled one day, the novelty of synthesizing Hardcaml down to discrete TTL logic on a custom PCB made this one of our favorite submissions.

Matthieu Michon [GitHub]

Matthieu, a professional engineer from France, built an elegant framework for solving the puzzles on real FPGA hardware using only the JTAG interface. His designs are board-agnostic and run on any Xilinx 7-series FPGA with sufficient density. What we particularly appreciated was his honest documentation of the debugging process: he encountered and resolved simulation/synthesis mismatches, and even opened a Vivado support ticket for a bug that he discovered in the JTAG TCL commands. His submission demonstrates the real-world engineering challenges of getting hardware designs working correctly, not just in simulation.

Rémy Citérin [GitHub]

Rémy, a university student at École Normale Supérieure in France, used Bluespec to solve multiple days—and then went further by benchmarking his hardware implementations against software running on his own custom out-of-order RISC-V CPU. The Day 10 Part 2 solution is especially impressive: he implemented Gauss-Jordan reduction with careful numerical stability handling (using GCD-based normalization to keep integers at 16 bits), followed by brute-force search over non-basic variables. His detailed README walks through the algorithmic transformations from recursive Python prototypes to explicit-stack Bluespec implementations. It’s a great reference for hardware algorithm design.

Robert Solomon Saab [GitHub] [TinyTapeout]

Robert, an electrical engineering student at the University of Toronto, took the challenge all the way to silicon. His Day 12 solution implements a clever pseudo-recursive backtracking algorithm that tracks placed shapes and orientations (in fact, solving a much more general version of the problem than was required to complete it on Advent of Code). What makes this submission stand out, though, is that Robert took his Hardcaml design and actually taped it out as an IC through TinyTapeout. His design was deliberately architected for minimal hardware usage to fit within TinyTapeout’s constraints while still taking full advantage of the hardware.

Satya Jhaveri [GitHub]

Satya, a professional engineer in Australia, produced one of the most comprehensively documented submissions of the competition—covering all 12 days with detailed algorithm explanations, complexity analysis, and implementation notes. Beyond the documentation, his solutions feature clever algorithmic insights: an O(1) formula for counting invalid numbers in Day 2, a heuristic to avoid storing O(N²) edges for Day 8’s dense graph, and a pipelined approach that reduces Day 9 from O(N³) to O(N²k). He also implemented a CSR graph representation with disjoint set union in Verilog for Day 11. For anyone looking to learn how to approach these problems in hardware, Satya’s repository is an excellent reference.

What started as a simple challenge to solve Advent of Code puzzles in hardware turned into something far more creative and impressive than we expected: custom CPUs, neural networks, discrete logic PCBs, and actual silicon. The range of approaches—from a high school student’s first FPGA project to a retired engineer’s multi-platform validation suite—shows just how wide this challenge spread. Thanks to everyone who participated, and especially to those who documented their journeys for others to learn from. We’re already thinking about how we could challenge everyone next year! Stay tuned for more.